So, what has a Jigsaw puzzle have to do with Net Zero, and why would anyone undertake a 42,000 piece jigsaw ?!

Financial Markets need clear, comprehensive, high-quality information on the impacts of Climate Change. This includes the risks and opportunities presented by rising temperatures, climate-related policy, and emerging technologies in our changing world.

The Financial Stability Board created the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) to improve and increase reporting of climate-related financial information.

However, four years after the release of the TCFD recommendations in 2017, there is still no standardisation or consistency in the disclosures of emissions reductions targets. In practice, this makes it challenging for investors and other stakeholders to understand the exact nature of carbon commitments and systematically compare company ambitions across large portfolios. In many cases, we also find that companies choose a target specification that makes the headline numbers appear significantly more ambitious than the actual commitment.

Earlier generations of targets were mainly focused on incremental carbon savings, often in anticipation of potential future carbon pricing. They typically aimed at improving carbon efficiency, with targets frequently being expressed in terms of reductions of emissions per unit of output or revenues (or ‘intensity targets’). Few companies were willing to make promises to reduce their absolute volume of annual GHG emissions – let alone publicly commit to timelines to cease emissions altogether.

However, under pressure from campaigners, investors, and governments, corporate targets have become much more ambitious in nature. Indeed, according to the UNFCCC’s Race to Zero campaign in 2020, over 1,500 companies have set Net Zero’ targets. These targets aim to bring a company’s residual emissions to such a low level that they can be balanced by the company’s removal of emissions from the atmosphere (whether through biological carbon sinks such as forests, or potential technological sinks such as direct air-capture systems).

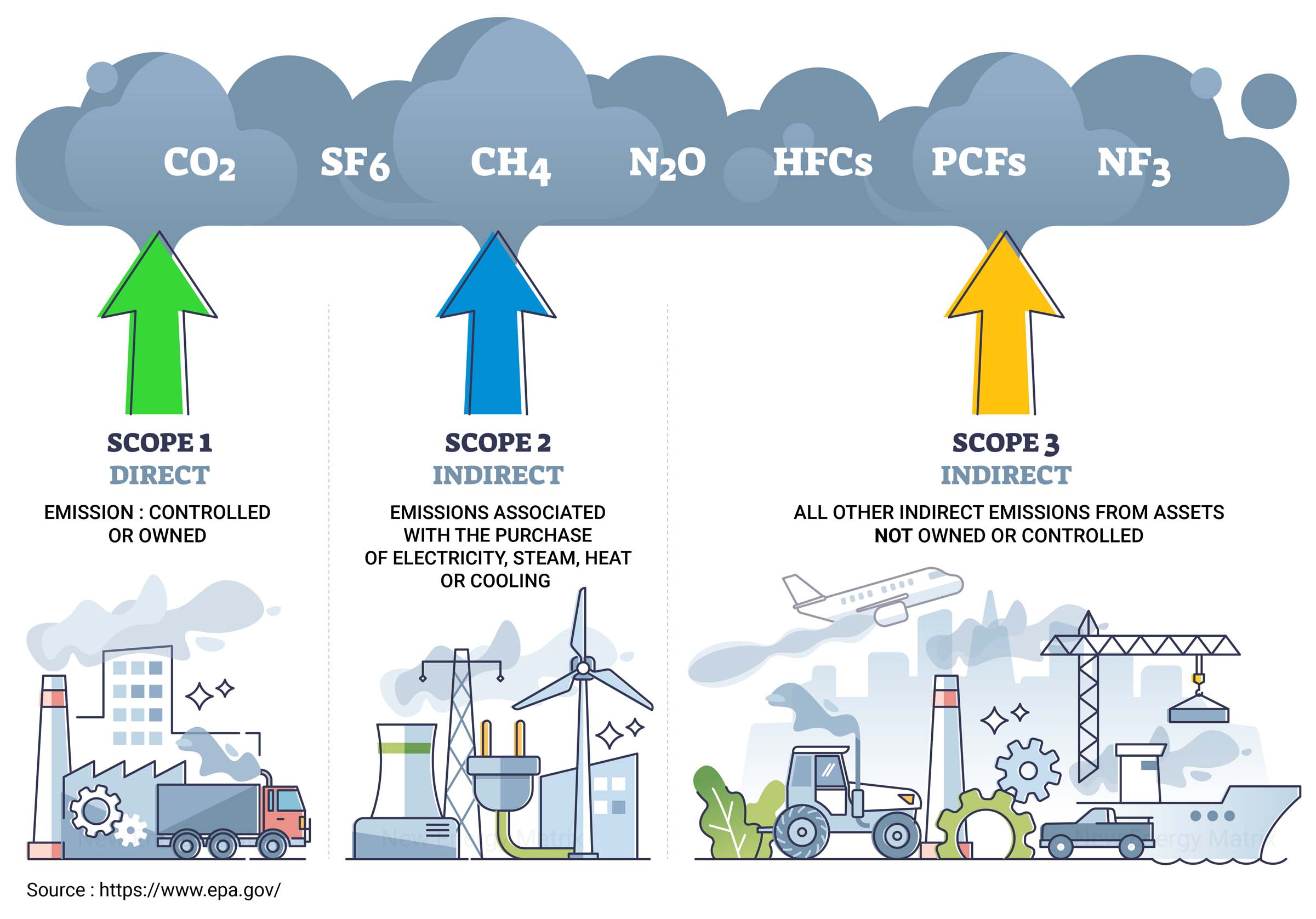

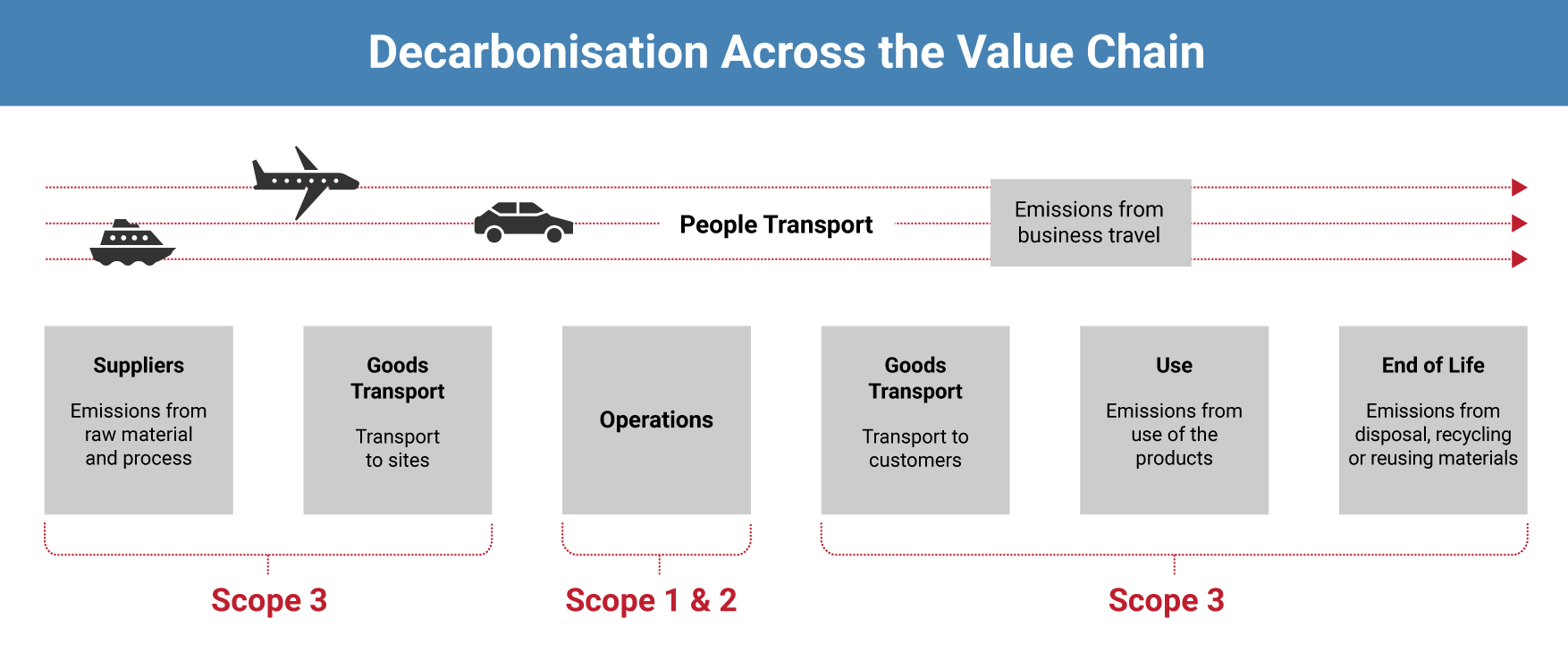

Some companies have also started to include value chain emissions in their targets, rather than focusing solely on their direct emissions (Scope 1) and their indirect emissions from electricity use (Scope 2). While such ‘Scope 3’ targets are still the exception rather than the norm, they are essential in some sectors like autos, chemicals, and oil & gas, where Scope 3 emissions typically account for the lion’s share of emissions associated with a company’s activities.

The problem with Scope 3 is that there are many actors involved in a particular supply chain, both ‘upstream of a particular company (suppliers), and downstream of it (customers, resellers). At the moment for most companies the setting of a Net Zero Target and the analysis and assignment of Scope 3 Emissions is a serious problem